Gardening for the Nectar-Fueled Flying Machines

Originally written for West Sound Magazine in 2014.

A hummingbird darts about the garden. Its long, willowy tongue flickers in and out of its beak in anticipation of the honey-sweet nectar. The miniature acrobat flies around, occasionally coming to a standstill in midair, its wings moving so fast, they disappear from perception. Cruising around, it zeroes in on its target — a bright, elf-size coral bell. The tiny bird gracefully moves in as its slender beak sinks into the flower. Drawing out a sweet reward, the hummingbird continues its delightful moves as it forages among the flowers. A glimmer of sunlight sparkles through a drop of nectar that escapes its beak. This must be ground zero for heaven on Earth.

It’s fascinating to watch the local hummingbirds in the garden, flying from flower to flower, using abilities no other birds possess. Their wings rotate in a circle, giving them the capability to move in any direction and hang suspended in midair. They can hover because their wings move back and forth in figure eight. People love watching them. Not only can they move from a standstill to top speed in an instant, but they also have the skill to fly upside down for short distances and maneuver rollovers when attacked from above. It’s likely the reason why these little ones are so fearless.

When the Rufous hummingbird returns from its annual migration, the male’s effusive antics are fascinating. He shows off his prowess to any female within watching distance. His loop-to-loops are superb as the little bird continues defying gravity. When the flying acrobat comes to a halt in midair, he lets out a series of chirps that sound like a cartoon character slamming on imaginary brakes. Stunt pilots could learn a few strategies from these nectar-fueled flying machines.

When the males leave and continue their migratory route, the females start bringing their brood to the feeders, watching over them like any mother hen. She will sit on a branch not too far away, ready to dive in and defend her children at the first sign of trouble. The juvenile males learn how to protect their territory with mock battles, and the feeders become crowded with squabbling young ones.

Spreading northward the last two decades, Anna’s hummingbirds are now year-round residents in the West Sound. Some believe that this species survives the local winters better because they consume more slow-to-metabolize insects and spiders than other hummingbirds.

As more people realize they have these flying gems year-round in this area, they offer feeders even in winter. However, for maximum health, plants providing nectar every month of the year are best for these tiny birds. Think of the feeder as an extra energy boost, not the main course, regarding their diet.

Providing shelter along with nectar-rich, tubular flowers will entice these birds to take up residence. They remember and revisit every new nectar source. Gardens that are insecticide-free provide a smorgasbord of insects and spiders, a sizeable portion of a hummingbird’s diet. In return, the birds keep the insect populations at lower numbers.

Winter Nectar Sources

A few plants provide flowers for Anna’s hummingbird during winter. The following shrubs are striking plants for the landscape, adding fantastic color during the seemingly endless, dreary gray days of the coldest season.

Royal grevillea (Grevillea victoriae), pronounced grev-ILL-ee-uh, has silvery-green leaves, russet-brown buds and fuchsia-pink flowers that bloom mid-fall and all winter long. You may notice a large amount of activity from the tiny hummingbirds darting in and around it on a warm November day.

Another mainstay for the winter garden is the winter-flowering mahonias. Blooming earlier than the native Oregon grape, Mahonia ‘Arthur Menzies’ and ‘Charity’ will keep the winter garden filled with long stalks of cheerful, yellow flowers and Anna’s hummingbirds returning to this rich nectar source.

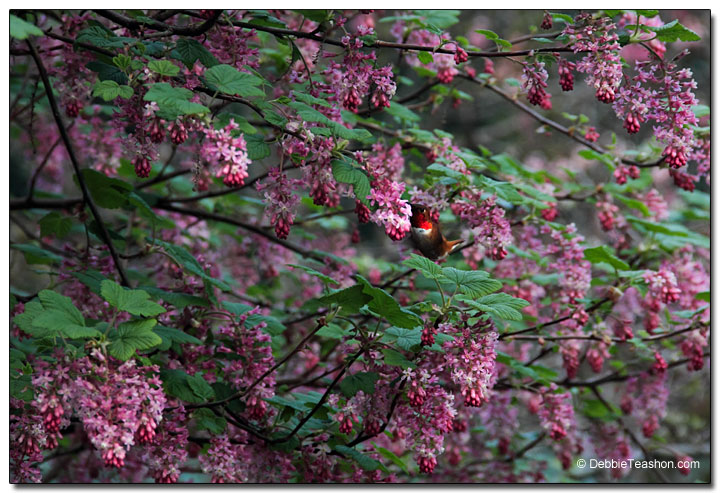

In late winter, two native plants, flowering currant (Ribes sanguineum) and Oregon grape (Mahonia aquifolium), blossom about the time the Rufous hummingbird male returns. The flowering currant lights up the Kitsap Peninsula with hanging racemes of brightly-hued flowers, while the Oregon grape gives a hanging raceme of loose, yellow flowers. Both shrubs are handsome natives that can fit into many Northwest landscape styles.

Other Key Plants

Beardtongue (Penstemon ‘Andenken an Friedrich Hahn’), bred in 1918, is one of the oldest hybrids in the genus, one of the best to grow and the most successful one ever introduced. The penstemon, mostly sold as ‘Garnet’, is a handsome evergreen plant, flowers from mid-summer to mid-autumn.

Cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis) has scarlet-red, tubular flowers and blooms on long racemes. Short-lived, moisture lover. Keep soil moist all summer.

Heuchera has a wide variety of species and cultivars. For the hummingbirds, choose types with red flowers — many are available in an assortment of foliage colors. Heuchera ‘Hollywood’ blooms in late spring and again in summer.

Fuchsias

Nothing in the garden says it’s summer more than hardy fuchsias and the hummingbirds who stake their claim. These perennials continue blooming until the first frost, serving their nectar over two seasons. Favorites in my garden include ‘Aurea’ with golden foliage and purple and red flowers. Another hardy upright is F. hatschbachii, which grows tall and leans over the garden like a fishing pole.

Fuchsia corymbiflora is a tender species from South America, where it grows into small trees. The large clusters of long, bright red, tubular flowers have an exotic, tropical look. Berries sold at the marketplace by the indigenous people of South America have a mild flavor reminiscent of ripe figs. Plant in a large pot and bring it into a greenhouse or unheated garage for winter.

Here’s my list of great hummingbird plants. What are some of your favorites? https://debbieteashon.com/2021/07/nectar-plants-nw-hummingbird/